KE: The film producer Lynda Obst once told me that she came up with the idea for the George Clooney/Michelle Pfeiffer romantic comedy One Fine Day, when she—overworked, exhausted—was lying on a massage table thinking that to meet a man she would have to literally crash into one with her car. Andrew Davidson, who I chatted with recently on the blog, opened his bestseller, The Gargolye, with a car accident that transforms his character, body and soul. And I have always been a fan of the late painter Carlos Almaraz’s oils depicting cars in flames. What is it about art and car wrecks?

| Now, I find that two very fine authors, who also happen to be friends of mine, have each opened their new novels with car accidents. Penny Vincenzi, the No. 1 bestselling British novelist, whose books are addictive and virtually impossible to put down (she’s doing this chat because she owes me for so many nights of lost sleep), uses a car crash in the beginning of The Best of Times as a device by which the characters become entangled in one another’s lives. |

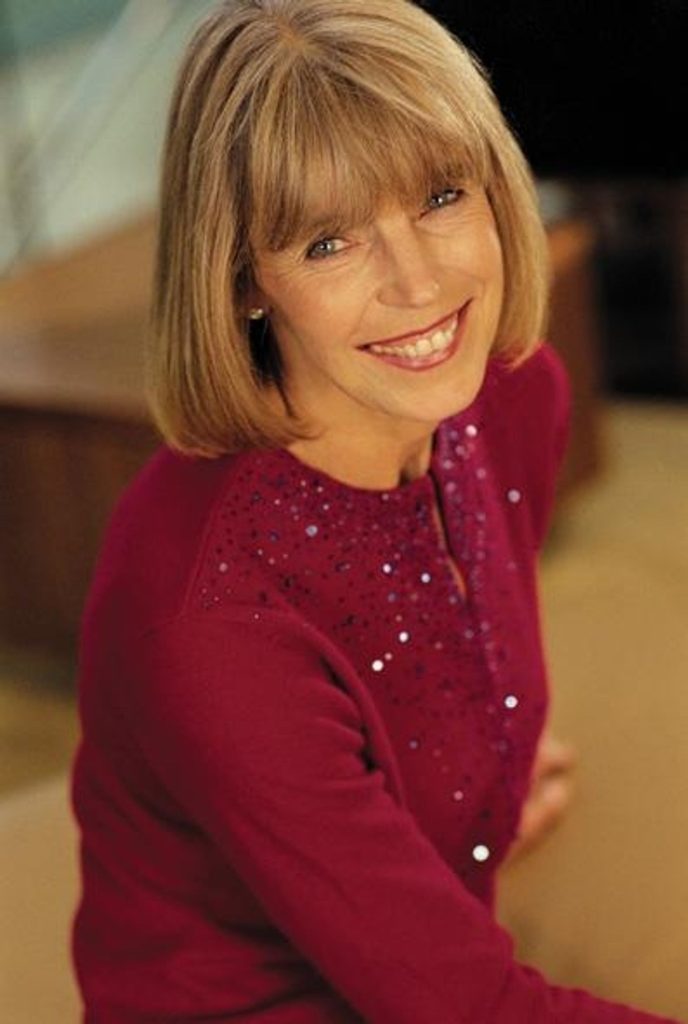

| Christina Baker Kline, Fordham University’s Writer in Residence, opens her acclaimed fourth novel, Bird in Hand, with a car accident that brings out the hidden alienation festering below the surface of existing friendships and marriages. I found the book impossible to put down and read it one night in lieu of sleeping. |

Ladies, could you please tell us what inspired you to open your novels with car crashes? Did the idea of opening a book with an accident inspire the novels, or did you have relationships in mind that you wanted to explore, and retrospectively decided to use the car crashes as the catalyst? In other words, was it the chicken first, or the egg?

PV: It was a real-life accident that inspired me to write The Best of Times. Well, two actually. The first was an accident that actually took place on the motorway I use all the time as I travel from our cottage in Wales to our house in London—or on this particular occasion to my publishers. I was nowhere near the accident itself; but stuck in the consequential tailback for almost three hours.

It is complete impotence; you can’t go on, you can’t go back, you are held suspended in time and place by Fate. I was lucky—not merely because I hadn’t been nearer the front of the crash, but also because my meeting was hardly crucial. What I had to endure was annoying, and made life a little more awkward, but no more than that. Around me were people more seriously affected: one young man said if he didn’t get to London in time to sign some documents at his bank by close of play, his business would go under. A couple were desperate to get to the airport—not just for a holiday trip, but to attend their daughter’s wedding next day in Spain. An elderly gentleman was on his way, driven by his daughter, to an important medical appointment he had waited three months’ for. All around me were seriously distressed people. Less serious were thirsty dogs, fractious hungry children, and lots of people in need of a loo.

And you know what? I thought: this is a book. About all sorts of people in all sorts of people, being taken into captivity by fate: and what would happen to their consequent lives. Like a husband perhaps, helplessly trapped with his mistress, in a place where he had no business to be, not at all where he had said he would be; like a bridegreoom, hurrying to his wedding; like an actress, desperate to get to a last-chance audition. Oh, my goodness!– as always, when this sort of thing happens to me, I guiltily stopped worrying about other people and started making notes….

KE: Penny, I am reminded of the story of the man who worked in the Twin Towers whose wife was calling his cellphone all morning on 9/11 to see if he was alive. He was, but was with a mistress at a hotel and knew nothing of the tragedy. When he finally returned her call, she asked where he’d been all morning, and he blithely replied that he was at the office!

PV: Oh and then the second accident was domestic; my daughter and her boyfriend had come to spend the night with us, so that he could be at an interview, an important interview– in London early in the morning. He was wearing his best suit as he sat at the kitchen table, having a late night glass of wine with us and showing us his carefully prepared CV—pages of it. .

And then—my daughter passing the table, knocked her father’s arm, as he lifted the bottle to pour a second glass of wine. Red wine. Which went all over the best suit. A light grey suit.

We sat and stared at it in horror; everything in that instant changed, from order to chaos. All our plans were scuppered—or so it seemed; the early, and therefore calm, start; the immaculate appearance, the beautiful presentation. And—possibly, or even probably—his chances of getting the job. All for the jog of an arm. Terrifying.

(I would like to reassure you that we managed; plunged the jacket into cold water—risky, but better than nothing—oh the wonders of the man-made fibre. We transferred his notes to my computer, admittedly with a sweatily difficult juggling of emails and attachments–oh, the wonders of technology–and printed them afresh. It was summer and we hung the jacket by an open window and my daughter completed its drying in the morning with a hairdryer. He wore a shirt of my husband’s –a little large, but we decided it didn’t matter; and he got the job.) But—what a jog of an arm can do. What an accident, a moment’s chance, can do.

CBK: When I first moved to the suburbs of NYC after years of living on the Upper West Side, with my husband and two young children, one of our first purchases was a minivan. I hadn’t driven in years, much less an unwieldy, seven-seat bus, and I was filled with anxiety. New Jersey traffic can be fast and unforgiving; caught in the maze of unfamiliar roads, I was constantly losing my bearings. My children’s lives were in my hands – my white-knuckled hands, that is, gripping the steering wheel. I was terrified of getting in a car crash that was my own fault and being responsible for maiming, or killing, my child or – god forbid – someone else’s.

Around this same time, I began writing Bird in Hand. The central character, a mother, gets into an accident in which a child dies, and this accident changes the (interconnected) lives of four people. Somewhere along the way I realized that I was writing this book as a way of exploring my deepest fears around this subject – and that those fears were too close. It was like staring directly into the sun; I had to squint and turn away. I put the manuscript in a drawer and only came back to it after several years, when my children were older and my worries had subsided. (For one thing, I’d become a fairly competent driver.) And I broadened the scope of the novel: the accident became a catalyst for the larger story rather than the story itself.

KE: I also happen to know that both of these authors are writing about infidelity from within stable long-term marriages that have produced many offspring. Penny has four grown daughters, and Christina has three young sons, and neither has traded in her husband for a new model! Bird in Hand puts marital infidelity under a brutally strong microscope, and yet the vision is not without compassion. The Best of Times also has married folk sneaking around. Penny has written about marital infidelity in her many books—enough, some might say, to place her in an Unfaithfully Yours Literary Hall of Fame. But she, too, writes with compassion for all parties, faithful and faithless alike.

Is it tricky to explore these waters from within a marriage (that one wishes to keep!)? Do your husbands eye you with suspicion? Have their friends warned them that you two know a little bit too much about this subject? Or does a solid marriage and domestic scene give you a secure base from which to explore the opposite scenario?

PV: Well, yes. Three things here.

1. I may have been long and happily married, but I have come across many many stories of people who have not. I have never, ever written directly, or even indirectly about anything real-life, but the bones of those stories stay with me, to be filled out with some quite different flesh. And you know what? To paraphrase Tolstoy, every unhappy marriage is unhappy in a different way.

2. I do have an imagination.

3. The escape into fantasy is a wonderful antidote to real life. Writing a book you can be beautiful, thin, witty, rich. You can meet incredible people and particularly incredible men. Who you can flirt with, lunch with, fall in love with, have passionate affairs with; all from the absolute safety and security of your study. Many is the time I have risen from a rumpled double bed in some luxurious hotel suite, a jeroboam of champagne at its side—shut the door behind me and gone downstairs with the dog—my only real-life companion in these adventures–to cook the stew for family

supper, feeling—I’ll admit– just mildly titillated, but absolutely virtuous.

CBK: In real life, I am something of a romantic – and happily married! But I also know that marriage can be hard at times, even under the best of circumstances. While I was writing this novel my husband, David, and I were, like many of our friends, adjusting to profound life changes: a new house, a new lifestyle, two small children, loss of autonomy for both of us, some loss of identity for me, a stressful job for him, a commute into the city. Some couples we knew, close friends, did not weather these storms intact. Why and how did these marriages end? The answers to these kinds of questions are always complicated.

At one point in my book a character wonders, “Who breaks the thread, the one who pulls or the one who hangs on?” In Bird in Hand I wanted to write about the complexities many couples deal with at this stage of their lives, whether or not they come through together. I wanted to show what’s hard about marriage and what happens when people can’t figure out how to communicate with each other. I wanted to follow my characters to all the dark and elusive places. Most of all, I wanted to talk about the nature of love and desire.

Though my husband read bits and pieces along the way, this is the first of my novels that he has not yet finished. (It’s on his nightstand still.) It isn’t autobiographical, but I think it’s still a bit hard to read. As you well know, novelists are like magpies – opportunistic scavengers who feather our nests with whatever we find lying around. I used my own life in many ways in Bird in Hand. I think that these four characters are all me, and they’re all my husband. They’re also lots of other people I’ve met. And no one at all. I felt like an actor (or perhaps several actors) writing this book: I truly inhabited these characters. I became them as I wrote.

KE: It is always fascinating for me to learn the genesis of a novel. The threads of a novel’s fabric are gathered from so many sources and the weaving process is such a complex balance of artistry, craft, and surrender to the unconscious, that it makes it challenging to try to explain. Yet the discussion is always illuminating.

Thank you, my friends, for participating.