From the first time that I read Bram Stoker’s Dracula in my teens, though I revered the work, I just knew that the character Mina Harker, Dracula’s obsession, was not satisfied with the role Mr. Stoker gave her—the quintessentially compliant Victorian virgin. I knew that there had to be more to her than that. (I knew that there had to be more to any woman than that.)

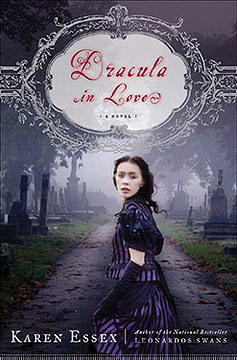

Anyone who has read my books knows that I am all about restoring grrrrl power to the historical record. In Dracula in Love, I decided to tackle a work of fiction, reexamining an iconic female character that had not been given her due. In a nutshell, my plan was to rescue Mina from Stoker’s sexist fantasy of the nice, cooperative girl, and empower her.

No one took this newfound freedom more seriously than the character herself. Honestly, I had no idea of how much power and autonomy Mina would claim, cutting me—her liberator!—out of the picture and doing her own thing on the page.

A little background: the late Victorian era was a time of tremendous change. Equal rights for women was a constant topic of discussion in legislative bodies, in the media, and in the home. In reaction to the freedoms and parity women were demanding, “society,” or “the patriarchy,” or whatever you want to call the keepers of the cultural norm, kept insisting that “good” women were feeble of mind and body and could not handle things like intellectual inquiry, physical exertion, or, God forbid, the vote. At the same time, opportunities for women were increasing rapidly because, frankly, they were needed in the exponentially expanding economy and the industrial workforce.

Naturally, I thought that “my” Mina would be leading the suffragettes in protest marches through the streets of London, going to university to get a degree, and telling the male vampire hunters to bugger off and let her enjoy some tasty vampire sex! After all, I was rescuing her from the “cult of domesticity” of the late Victorian era and putting her on the cutting edge of change!

Not so. It seemed that Miss Mina was still clinging to out-moded ideas of womanhood. The more I tried to write her as a liberated woman, the more she rebelled, screaming in my head that I was no better than the bossy Victorians who told women who they should be. I tried to reason with her. “Mina, darling, we have a deadline. I’ve got this narrative down pat, so you just cooperate!” No dice. As long as I persisted in telling her that she must politicize and rebel, she downright refused to send any words my way. I spent months writing pages and then throwing them away. I kept referring to my 150 page painstakingly constructed outline, written from Mina’s perspective, but everyday it seemed more irrelevant. Finally, I had to throw it away.

One day, I sat down with a notebook and pen and asked Mina who she wanted to be. I was very, very quiet, letting her voice come through so that I could hear what she’d been trying to tell me. First, she insisted on starting out as a very traditional woman with a deep desire for hearth, home, and family. To my shock, she told me that she was in line with Queen Victoria, who did not approve of all this emancipation and thought that suffragettes needed a good spanking! She informed me that she was in total opposition to another character I’d created, the feminist Kate Reed, a journalist who was always trying to get Mina to adapt to the ways of the New Woman. Mina made me see that as an Irish orphan living in England, her choices were limited, and the one thing that could yield her a decent life was not the right to vote in an election but marriage to the right sort of man. “Put yourself in my shoes!” she demanded.

And so I did. Like a reluctant parent, I realized that I had to let Mina evolve at her own pace and her own discretion. In the end, I’m happy that I capitulated because she has a very satisfying character arc. If she’d started out the independent woman I wanted her to be, she would have had nowhere to go. Because I agreed to do it her way, she used the length of the narrative to learn and grow. Eventually, after much trial and error, Mina learned to accept her intelligence, her gifts, and yes, her powers. In the end, she actually embodies the Nietzschean quote with which I begin the book, “You must become who you are.” That is my belief for Mina, for myself, and for all of us, whether male or female. Otherwise, a great deal of suffering ensues.

Dracula in Love was my sixth book but the one in which I had a stunning learning curve, and that was to let go of the reins and allow a character room to breathe, grow, and speak. In her own mystical way, Mina taught me the true meaning of Nietzsche’s mandate, when I’d anticipated that it would be the other way around.

*This post was originally featured on two excellent and inspirational blogs about the writing process:

http://blog.WritingSpirit.com/

http://writerunboxed.com/